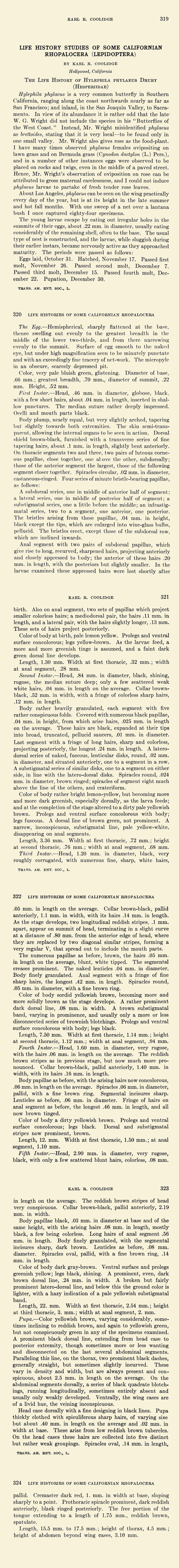

The Life Cycle of Hylephila phyleus

September 22, 2020 - On September 19th, in my backyard in Long Beach, California, I followed two female fiery skippers as they oviposited on Bermuda grass I had recently laid as sod in a strip along my patio. I was able to take five blades of grass with eggs on them. These were placed in a plastic cup with a lid, and I affixed a label with the date. I have five medium-sized pots with grass ready to serve as larval food plants. Based on the detailed life history of Karl Coolidge I've provided below, eggs laid October 31st hatched November 17th, so I expect my eggs to hatch in 2-3 weeks.

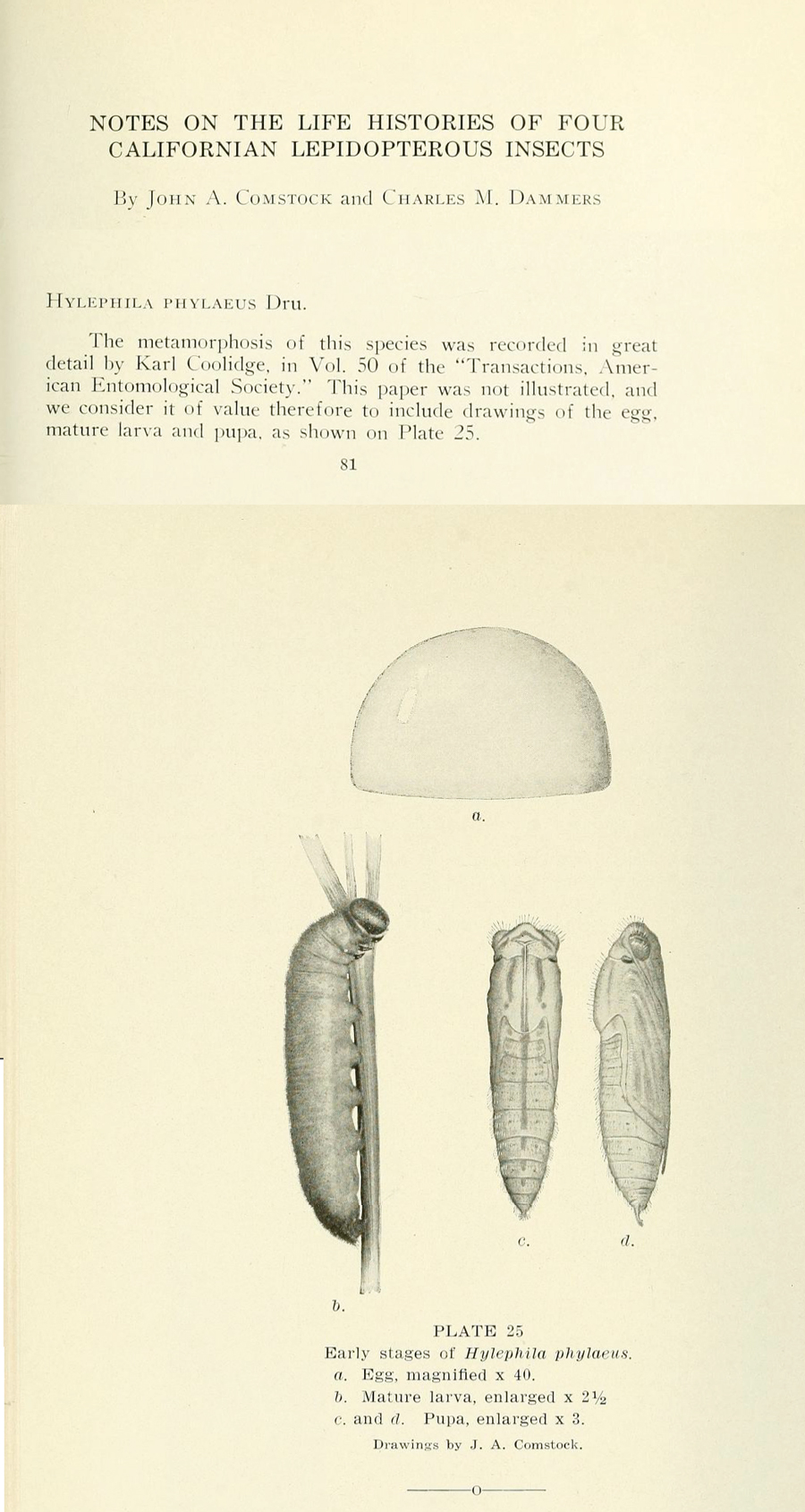

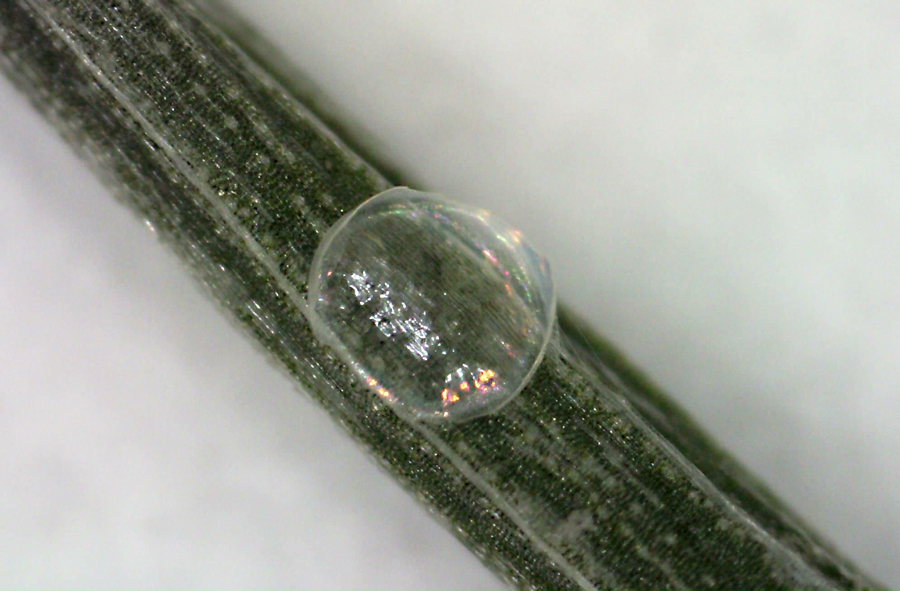

Coolidge writes that while the surface of the egg appears to be smooth, under high magnification it is "seen to be minutely punctate and with an exceedingly fine tracery of net-work." I was able to magnify it 230x using a Dino-Lite Edge microscope, and as the image below shows, there is indeed some texture visible. This is just about as close as my microscope can get. The image is actually a composite of several shots (basically focus-stacked), and the original is nearly double the size of this one, but I think this is fine for the web. Using the scope's measurement tool, the eggs are approximately .75mm in width. Coolidge has the base of his at .66mm and the greatest bredth at .70mm. He aptly describes the eggs as hemispherical; they have a flat base adhering to the grass blade. I've found that females can be skilled at finding a "good" green blade upon which to deposit an egg within a thick thatch of grass, curling their abdomen and moving over and past brown blades to find green ones. Then again, Coolidge notes that he has seen them oviposit rocks and twigs, so there's that.

I'll be following the advice of Peter May in A Handbook for Lepidopterists regarding the care for these eggs. That includes using a tissue liner in the plastic cup; watching for hatching larvae at least twice a day; allowing them to eat their egg shell; and transferring them to fresh grass as soon as I'm satisfied they've finished with their eggs. I've made half-hearted attempts to rear grass skippers before, but got nowhere. Hopefully these eggs are fertile, and with some attention and care I can get these through the transition from egg to a larva on living grass. Gordon Pratt has told me rearing from eggs is difficult, and I've seen that many times this year with many species collected as eggs.

This was published in December, 1924 in volume 50, no. 4 of the Transactions of the American Entomological Society. Comstock and Dammers took it upon themselves to provide illustrations (below) in the Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, vol.32, pp.81-2.

A tiny Fiery Skipper egg on host Bermuda grass, October 3, 2008.

September 25, 2020 - The drawings by John Comstock were published in 1933 in the Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, (vol.32, part 2). In 1926, Comstock had written in that journal, which was affiliated with the L.A. Natural History Museum, that "the complete metamorphoses of a large number of native species is entirely unknown." Over the next decade or so, he and his good friend Charles Dammers would go a long way towards rectifying that.

In the Los Angeles area at that time, there were quite a few talented lepidopterists exploring southern California and beyond. The Lorquin Club, founded at the Southwest Museum in 1915, moved to the L.A. County Natural History Museum in 1927 and became the Lorquin Entomological Society, with Comstock as President. This was the year he published The Butterflies of California. At this time, Chris Henne was young and active; Karl Coolidge had moved to Pasadena in 1920; F.W. Friday, Charles Ingham, J.D. Gunder, John Garth, and C.N. Rudkin were among the knowledgable local lepidopterists. Don Meadows made Catalina Island his laboratory. "New discoveries" by then tended to be aberrants, as some 75 years had passed since the days Lorquin began sending his catches to Boisduval in Paris and other European experts. So under Comstock's leadership, focus began shifting towards understanding southern California butterflies by learning the secrets of their life cycle. This meant identifying larval food plants and rearing each species from egg to pupa, documenting everything in detail. The quarterly Bulletin became a treasure trove of information about the immature stages of our southern California butterflies.

Early efforts from 1926 now seem rather random: an egg of this, a pupa of that, a host plant identified. But in 1928, Comstock began to hit his stride, publishing detailed information on the egg, larva, and pupa of dozens of butterflies over the next seven or eight years. This obviously required not just rearing these butterflies, but carefully documenting the process (in microscopic detail, with measurements) and illustrating the unfolding story. Comstock had taught insect illustration - see his fine fiery skipper illustrations above - but it was Dammers who began producing paintings and drawings that would become familiar to generations of California butterfly enthusiasts. In a 1929 article descibing the early stages of nine butterfly species, Comstock, who apparently did the drawings himself, wrote that "nearly all of the butterfly larvae and ova recorded in the foregoing paper were brought to our attention by Commander C. M. Dammers of Riverside, Calif. We take this opportunity of again extending our thanks to him." That tells us something about Dammers' early contributions; he was much more than an illustrator. By early 1931, Dammers was Comstock's co-author on a paper, one of 33 such articles. As far as I can tell, it isn't until the next issue, in the summer of 1931, that we see Dammers' illustrations in print. But he had been doing much of the crucial work behind the scenes.

Commander Charles H. Dammers was a retired British Royal Navy officer living on 20 acres in Riverside at this time, after having lived on a ranch in Argentina. He got out into the field, finding butterfly (and moth) host plants, collecting eggs, larvae, gravid females, or pupae, and rearing them back in his garden and greenhouse, documenting it beautifully. If you have either the Emmels' Butterflies of Southern California or Garth and Tilden's Butterflies of California, you have seen many of his illustrations. Some of his early works were donated to London's Natural History Museum; over 300 went to the Los Angeles MNH with his large insect collection.

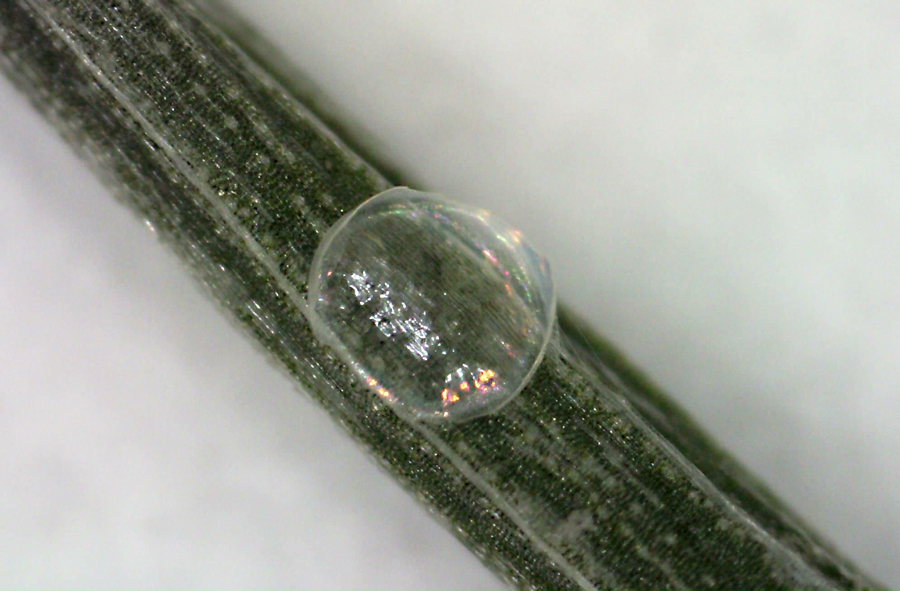

September 25, 2020 - So, just six days after the female oviposited on the grass, which allowed me to collect five eggs, I've suddenly got one larva out of the egg alive that I've successfully coaxed onto a fresh blade of grass; one in a transparent egg about to hatch; one that is still opaque; and two that I cannot find at all but may be in the curled grass blades.

Uh, this wasn't good news just 6 days in. It's empty. But hardly eaten.

This one is ready to go: that's the head in the transparent shell. The "two to three weeks" timeframe I was expecting is out the window. Coolidge measured the first instar head at .46mm, and the egg at .75mm, so that's a big head!

I found a tiny dot on the paper towel I put in the cup, and under about 100x magnification this is what I was seeing. Is it alive?

It moved. I got some fresh grass, and with some coaxing it moved onto the blade. I got more grass and put this one in a container alone. I put fresh grass on tissue in another container with the other four blades of grass, so hopefully I'll end up with at least two viable caterpillars. My issue now is when to transfer them onto the potted Bermuda grass. More to the point, how do I transfer them to live grass and still document their development, esp. if they make an obscure nest, which they certainly will? How did Coolidge and Dammers do it?

September 26, 2020 - Checking the grass clippings this morning, I saw that there were two larvae that had hatched and were alive in the cup, and the other cup had the egg that was about to hatch. I decided to put everything on potted, living grass, since cuttings were drying up rapidly and the larvae probably want to silk up a fresh blade. The photo below is one of the two I moved to the fresh grass.

A recently emerged larva. The patterning of the hairs, or setae, and other features is described above in the Coolidge article.

October 7, 2020 - Well, I'm not finding them in the grass! Glad I started this page to document the process.... But I'll keep searching and if I have to start over, I will.

October 13, 2020 - I took the potted grass apart completely looking for any sign of the larvae in nests. Nothing. I have a hunch that a predator got to them. So, I learned to use a lot less grass, for one thing, since it was a lot to go through to keep track of them.

©Dennis Walker