Danaus plexippus plexippus

Monarch

In California, the monarch is best-known for its annual migration to the coastal groves where it roosts in clusters that have long been a tourist attraction. monarchs east of the Rockies migrate to and from roosting sites in Mexico. In our area, movement is generally northward towards Canada and back as temperatures allow (they don't do well in freezes). Where I live, freezes aren't an issue most years, and we may have monarchs all year. The larvae eat milkweed leaves and flowers, many of which contain toxins (cardenolides) that make most of the adult butterflies distasteful to predators. The bold coloration of the caterpillars advertises this toxicity to would-be predators.

This is an excellent butterfly to attract to a garden, simply by planting milkweed - Asclepias species - preferably a native. For California, good choices include fascicularis (narrow leaf milkweed, the best in my opinion), eriocarpa, and californica. I plant fascicularis in the garden every year now, and can't imagine not having at least a monarch or two present and lending the garden a more regal air. Non-native curassavica is widely available at nurseries, and it will attract monarchs even through the winter, but it should be avoided in our area. It's a good thing that native milkweed in your garden dies back part of the year, since this rids the area of plants infected with pathogens that afflict monarchs, in particular OE (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha), a protozoan whose spores accumulate on the plants.

This monarch is taking nectar on host milkweed at El Dorado Park, August 5, 2005. Unfortunately it's on curassavica, a tropical species which should be torn out. (One of my older photos but I've always liked the background colors.)

Freshly emerged in my garden, May 25, 2010.

A male monarch at El Dorado Park in a patch of milkweed, August 5, 2005. Males have thinner black lines along the wing veins and a patch of black scales on each hind wing.

A female monarch that had recently emerged from her pupa in my garden in Long Beach, October 26, 2005. One benefit of raising them yourself - fresh models!

Starting in 2005 I began planting plenty of milkweed in my garden to attract monarchs. This worked well, and I have watched them go through their life cycle many times. This is a monarch egg on milkweed.

A first instar monarch caterpillar that had recently emerged from an egg. April 13, 2011.

Second instar monarch larva on the same plant as above, April 17, 2011.

Another monarch caterpillar on its foodplant.

The monarch chrysalis is jewel-like with the gold and black accents against the jade color.

Another monarch pupa not long before the emergence of the adult butterfly.

Monarchs use several types of milkweed plant as caterpillar food plants, but among their favorites - and the one I most recommend people plant in their gardens - is narrow leaf milkweed, Asclepias fascicularis. This photo shows the flowers in bloom.

Asclepias fascicularis growing at Trout Pond Trailhead south of Lake Cuyamaca.

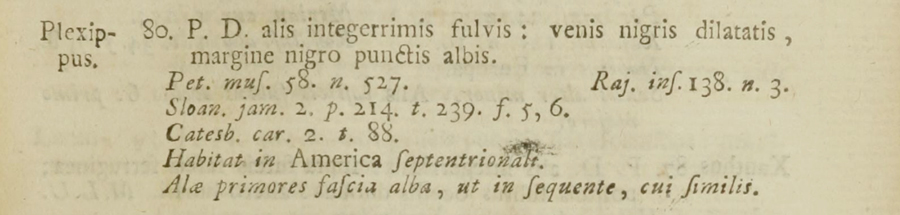

The naming by Linnaeus.

Plexippus was placed within the Danai, one of six divisions ("phalanges", probably meaning a phalanx or unit, from the military units in the Greek armies) within Papilio, which was within the Lepidoptera. Within the Danai, Linnaeus had two further divisions: the Candidi and Festivi, characterized by wings white and variegated, respectively. The butterfly had been known and illustrated from the Americas, but Linnaeus was the first to give it a formal name within a system of classification. From the

Systema Naturae, Vol. 1, 10th edition (1758), p.471.

©Dennis Walker